By Martin Brentrum – First Published Rod&Rifle Vol. 7 Issue.3

Steve Lowrie, Basil Dynan and myself had walked into the NZFA hut by torchlight on a Friday night. The alarm stirred us at 5 a.m. next morning. No-one lingered in the pit. Breakfast was had, pikaus packed with an air of keenness and purpose.

We left the hut in the grey half-light of dawn shortly after 6 a.m. Stars were out and the morning windless. Distant roars drifted up the valley below. The day was full of promise.

The intention that morning was to hunt the mountain beech-clad spurs of the mid-forest, for it is on the shoulders of these spurs, where the gradient levels off, that roaring stags establish their territories.

The track dropped into the creekbed and we moved quickly, keeping an eye out for a handy deer on the river slips. At a place where the stream was joined by another branch, we separated. Bas would hunt up this stream while Steve and I hunted up a spur twenty minutes down-stream on the true right.

Initially the going was slow through high pampas grass, beech deadfalls and patches of dense fern, but as the creek sounds became fainter the spur opened out nicely. Typically, the sides were clothed in dense pampas grass. Sidling in this country tended to be noisy. At most other times of the year the spurs and ridge tops were not necessarily the best places to hunt, but during the roar they’re hot spots.

The roars of a mature stag from well above instilled urgency in our movement. As we paused to listen, I estimated that twenty minutes steady climbing would put us close to him. Steve grinned as I gave the thumbs-up sign and signaled forward.

Over the next rise, I startled a young stag which wheeled and lept gracefully over a log and vanished down the side. There was no time to raise the rifle, anyway, he wasn’t our quarry, just a hopeful four-pointer stirred by the irresistible mating urge that besets his kind, not big enough to do battle with the older fellows, a seeker, ever on the lookout for an unaccompanied hind, but his turn would come; maybe.

Higher up the beech thinned out. Here moss and leaf litter lay underfoot, tanekaha saplings were thrashed to ribbons, there were deer prints everywhere and best of all, the strong acrid smell of stag was all around.

Steve looked on as I raised the roaring horn, swallowed once or twice and roared. The stag answered furiously, not from above us, but from across on another smallish spur that plunged steeply down from the tops., leveled off, and then fell away in a succession of bluffs, into a fork of the sidecreek below us.

I left him to his thoughts for a minute or two, during which time he called again., then I roared loudly and added a few grunts. The reply came straight back, a wild full-throated roar followed by grunting and the sounds of a bush being thrashed. I roared. Back came his answer and more thrashing. He was getting really worked up.

We were both enjoying every minute of this but in a quandary as to our next move. To cross over to him would create much noise, the wind was likely to prove fickle and above all, he would undoubtedly have with him one or two vigilant consorts. The best tactic appeared to be to climb up to the main ridge and come down the spur on top of him.

He interrupted our indecision by roaring again. I counted to ten and answered. His reply blared back accompanied by more wild thrashings. I raised the horn and came back at him with a succession of loud grunts. That must have been the final insult, for shortly after his raucous reply we heard the clatter of rolling shingle.

Though we couldn’t see clearly, it was apparent he was crossing the steep shingle scree on the face opposite. Was he going to sort out this insolent trespasser? We hoped so!

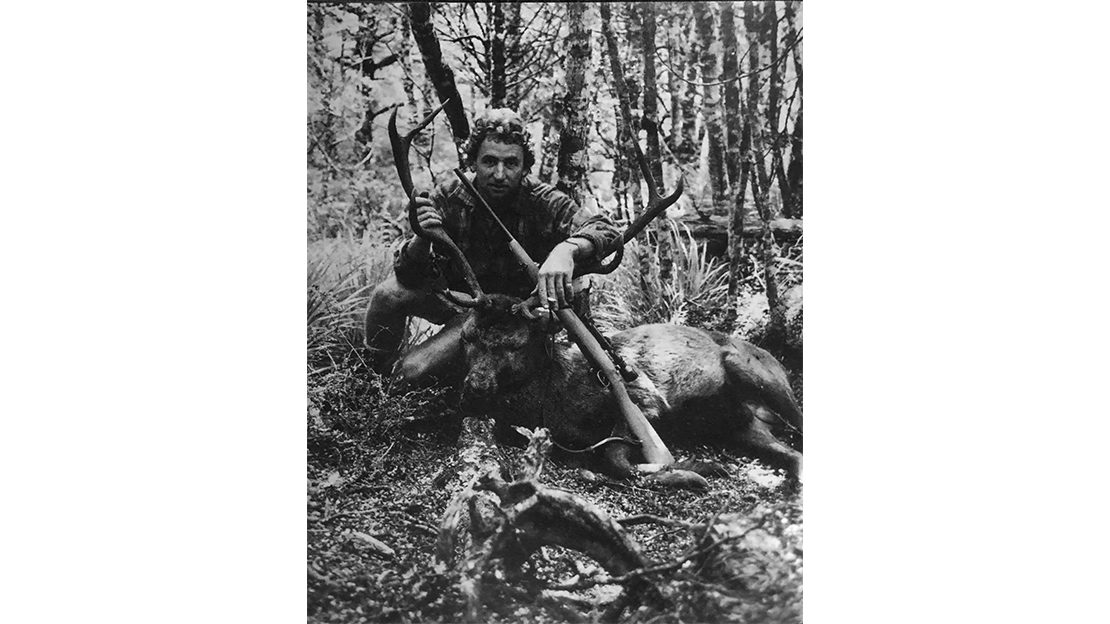

I indicated in whispered tones that we’d move forward to find a better place to intercept him in case he had decided to take the initiative; somewhere with an unimpeded view to the ridge. We’d gone maybe thirty metres, threading ultra-quietly when a twig snapped and the pampas grass swished just ahead. And antlered head peered quizzically at us, eyes and ears on full alert, searching out the unwanted intruder. Right then it was time for instant action. Reflex took over; the .257 was up, bolt closed 30-30 reticle centred on his upper neck . . . . bang. He collapsed, poleaxed, and never even twitched. The bullet had smashed his spinal column; a fine beast and reasonable ten-point head by Ruahine standards. His bold approach had been his undoing, but what a satisfying climax to an action-packed stalk.

On reflection, I regretted taking the shot, but Steve would have none of it. The was better than he’d hoped for. Strong, fit enthusiastic and totally unselfish, he had the makings of a real good hunting mate.

We sat there, reliving the stalk, marveling at how quickly he’d got across to us, admiring his powerful well-conditioned physique. He’d performed magnificently in the classic tradition of the rutting stag.

We spent a long time taking photographs, then haunched him. Steve volunteered to carry the load down to the creek. I said I’d do the same for him someday and followed with the pikaus, antlers, and rifles, wondering who’d got the best of the deal.

Partway down the ridge, a red beech deadfall had toppled into the foliage of another. I shinned up this convenient ramp, poked my head and shoulders above the canopy and roared long and loud. Three stags answered from across the valley. Soon the trio were going so well that they didn’t need my encouragement. One seemed to be roaring from an area I knew well; a largish bench of predominantly kaikawaka and tanekaha. Goaded by the fellows downriver he was becoming most unsociable.

We made haste toward the creek but encountered difficulties getting down the last drop of twenty metres, and had to push through thick scrubby stuff for a couple of hundred metres to the other side of the spur, where we were able to let the haunch go and slither down after it to the creekbed. There we hung the haunch in a shady thicket.

Ten minutes downriver we left the creek again and scrambled partway up a scree slope to avoid clawing through the initial morass of pampas, lawyer, and deadfalls. From there it was a simple matter of crossing onto a small spur that led to the edge of the kaikawaka bench. Twenty minutes climbing put us at the verge of the flat where we paused to assess the scene. The stag was roaring regularly on the far side of the terrace against the hill.

The question now was whether to stalk in or attempt to lure him towards us. To move in close was to risk being spotted by his hinds, and to roar at close quarters might make him suspicious.

I chose the second option, turned to face away from him and roared. He answered back, infuriated. I left it a minute then roared again, not loudly; instant reply. I grunted several times in the other direction. He went berserk.

These exchanges of pleasantries continued, but he began moving across to our right and further away, as his subsequent roars indicated. Again the dilemma, . . . . his hinds were moving away, drawing their master with them. They were suspicious or maybe he actually was shepherding them away from what he took to be another suitor. Whatever the reason he still appeared reluctant to leave without a fight.

I signaled Steve to stalk in while I kept the stag interested. He expressed doubts but didn’t wait for a third set of instructions. I retreated some distance and roared loudly. The replied raucously. I waited a minute then roared again. He roared. I left it a bit then let rip with a succession of lusty grunts. The ensuing silence was shattered by an almighty bang. Immediately I roared loudly, waited and roared again, maximum volume.

Another bang, ‘a finisher offer; I guessed, and continued to roar as I moved over to check on progress. Steve appeared from above me in the pampas grass.

“What happened?” I asked.

“The stag’s just below you,” he said. “Got him with the first shot. When you kept roaring the hinds didn’t know what to do. I had a shot at one but I think it missed. She was standing behind some pepperwoods.”

“How many were there?”

“It was hard to tell, I counted three, but they seemed to be going everywhere.”

The stag was a beauty. A very nice eleven pointer, considerably better than par for the course. I was rapt; Steve doubly so. We photographed him where he lay, dragged him onto a clearing for more pictures and finally, began the butchery.

I wondered aloud, whether we needed all this meat. It was, after all, stag meat; not the choicest venison around, and the journey back to the hut was long and mostly uphill, not to mention the trip home. The stroll back to the hut carrying haunch, antlers, pikau, and rifle, at least the thought of it, was bothering me. But Steve was adamant that as he’d shot it, he was going to carry home as much meat as he could. I remembered my offer that morning and observed that Steve was doing his best to make the carcass as bloody as possible as he gutted it; admirable spirit.

All this time I’d been roaring intermittently, and now as I stood there holding the stag steady for Steve, an earth-shattering roar from very close staggered us both.

My mate told me to ‘get after him’. My first thought was to grab the camera and put on the telelens. As an afterthought, I slung the rifle over my back.

Fifty metres away I came over a small rise and crouched by a rotten log. Had he not roared at that moment I might have had difficulty spotting him. He was sixty maybe seventy metres away across a small hollow and slightly above me, standing behind a dead leaning beech trunk amidst the ever-present waist-high pampas grass and partially screened by light shrubbery. A stalk with the camera was not practical, not with a light reading of F2.8 at 1/8 of a second. But what were his antlers like? For several minutes they were obscured, till he turned his head. My heart began to move faster. There were three good looking tines on each top.

As things stood at present there was no chance to shoot. But when the sounds of Steve chopping at the neck of his beast reached up the stag looked to get decidedly suspicious. In retrospect, it may have been the ease with which we’d obtained our kills that caused an over-casual approach now, maybe I made a mistake, maybe it was bad luck, but I decided to shoot quickly if I could pick a gap through the foliage. When the stag moved away a few metres and paused, I thought I had that gap, and fired. That was the last I saw of him. There was no indication of a hit, no blood, nothing. I could only surmise that the projectile’s flight had been affected by foliage in its path. During the course of a thorough search, I twice rechecked the firing zone to confirm that I had pinpointed exactly, the spot where the stag had stood. Light, foliage, discernible through the scope only with careful scrutiny, bore this out.

I suppose I felt a bit rueful over that bungle; grateful though that I hadn’t wounded and lost him. Steve was surprised that the stage had been so close.

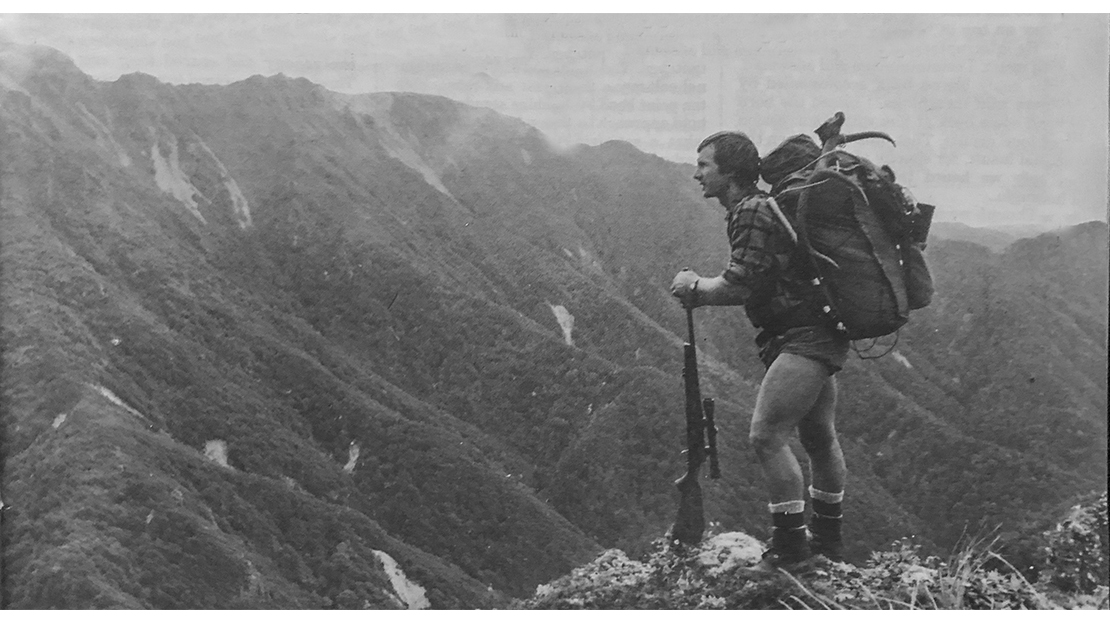

I shouldered the haunch and we retraced our steps to the river and the first deer. We struggled for an hour or so each with haunch, pikau, rifle, and antlers but decided to leave the venison in a tree forty-five minutes from the hut. The loads were awkward, and we were pretty knackered.

Bas was most impressed with our haul. He’d had an interesting time and had enjoyed the country. He’d got a shot at a hind at fairly long range but was sure he’d missed.

In the hut that night we relived the memories of what had been an enthralling day. It had been Steve’s first experience of hunting roaring red stags. For me, it had been one of those days you feel you earn occasionally for all the times your efforts go unrewarded. That Steve was there when things went so well, was a bonus.

Sunday saw us headed for the venison at first light. Steve and Bas offered to bone it and cart it up to the hut while I did a hunt with the camera and had another look for my stag.

Back at the hut by mid-day with no story to tell, I had a brew and a short snooze, and we packed up and set off around 2 p.m. The loads were staggeringly heavy, but thoughts like “I’m not enjoying this; why and I doing it?” – were forgotten once the packs were in the boot and Bas pointed the car towards home.

SHARE YOUR BEST PICS #NZRODANDRIFLE