By Graeme Omlo – First Published Rod&Rifle Jul/Aug 1995.

The date was set for an early July trip into the Douglas River, Westland. Joining me were John Gilchrist my hunting partner and his friend Joy. This was my third trip into the Douglas, while John had his first taste of West Coast hunting last year, when we did a foray up the Wanganui River. A vehement reaction came after a few days on the hill, when he announced, “I’ve been in some horrible situations, but this takes the cake.” Westland’s mountains can have that effect.

I think we all felt that way when the chopper had departed and we were left floundering in thigh deep soft snow, encompassed with the real silence of a frozen landscape.

Once camp was organised and the fire throwing some warmth all did not seem so imposing.

With all mountain pursuits, the weather plays the major role, so who could complain when we set out to clear skies. The night’s freezing temperatures had crystallised the snow’s surface, but had done nothing to harden its overall texture. Muscles were taxed as we ploughed up river, grateful for frequent stops to glass. Late the previous afternoon two thar had been spotted high on the opposite faces at around 1600 metres. Today’s glassing sessions brought further sightings, all high. Some animals had crossed the valley floor and hoof prints of big bulls encouraged us to look and look again. We never did catch them low down. In all probability they travelled at night.

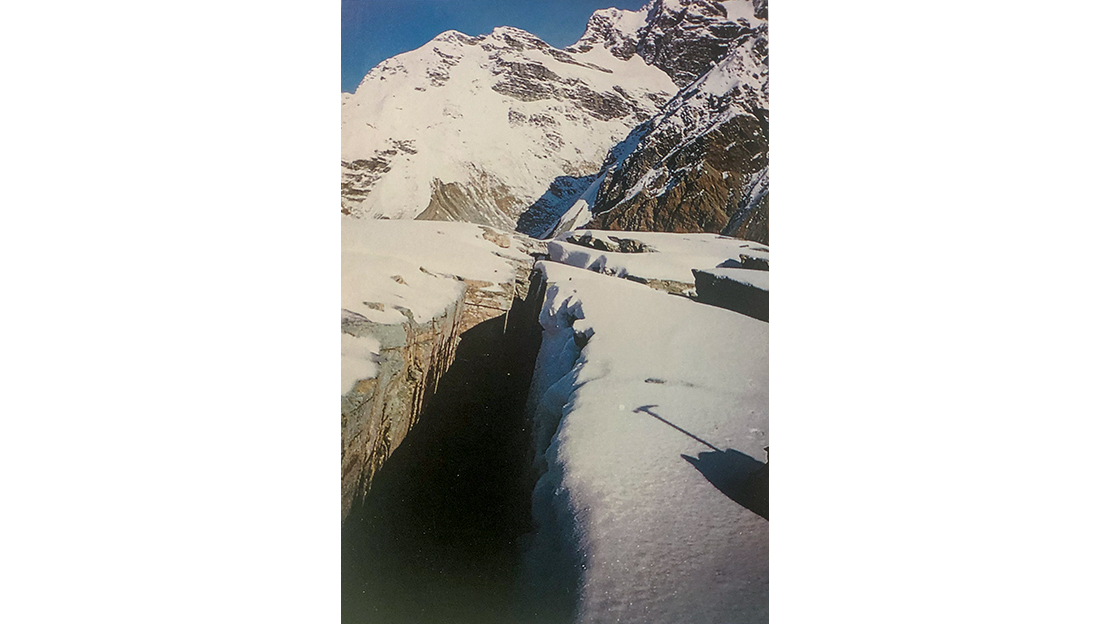

Further on, the glacial lake nestled, between bluff systems. This gave us the day’s easiest walking, as the frozen surface layered with snow meant speedy travel. The Douglas glacier made a spectacular sight of blue ice hanging in great folds, with Mt. Sefton as chief sentinel, rearing above.

Heading back with the heights bathed in a pink evening glow of the setting sun, we located an intensive area of thar tracking above the lake’s western end. No thar were seen, mainly due to our low viewing angle.

Next day a serious attempt to climb higher led to some unpleasant scrub bashing. Hidden traps, in the form of doubled over bushes weighted down with snow left us floundering and cursing when we fell through it. These were real energy sapping conditions. We now realised the effort required if we were to get amongst thar. At last we reached the scrub fringe. It was here that John decided to flag it. His determination being governed by the fact that he could rest on his laurels, content in the knowledge of a 360mm bull on the wall at home.

If anything the snow was softer here, due no doubt to the amount of sun this face receives. Dominating this area is the Pommel, a real Jew’s nose of a peak. Thar were in view on the higher slopes. Of interest was a group of seven bulls, black bodies obvious against the snow and tussock. They were moving around on the scattered areas of available feed.

Although those thar were a real draw card, the going was painfully slow. At times waist deep, trying to push up hill, ended my chance of making it. I was literally “stuffed” and the short winter days didn’t help. I reluctantly turned my back on them and started to sidle westward. Here a series of benches give way to rocky outcrops, overlooked by notable peaks. On reaching an abrupt edge, where the ground suddenly became unnegotiable, that old gut feeling prevailed. I felt I would see thar. A vertical grey bluff loomed above the gut ahead. I eased my head through sun bleached tussock. There, straight across lay a bull, staring hard my way. Almost immediately, another more mature bull unsighted till then, started to run. The first bull, a rock statue, still lay there. My attention went back to the one with trophy potential. He poised a couple of times, not positioned for a telling shot, but I got a chance as he rounded an outcrop and stopped, virtually front on. He reacted to the shot, showing a bull thar’s toughness, by turning and moving away to disappear behind a fold in the face.

Panic had taken over the other bull. He was joined by three others, another young bull, a nanny and her kid. They knew where to head, filing swiftly down into the scrub belt, chased by dislodged rocks. I stood there, knowing that if my trophy was dead and caught up I could kiss him goodbye as far as recovery went. Dropping down a few metres to get a better viewing angle, I was suddenly witness to a free falling thar, hell bent on flying. One bounce and he was out of sight. An awesome spectacle and one to serve as a warning on the effects of gravity if we ever slipped.

Wet, weather worn rock, ice and avalanche debris stopped a descent to where he had disappeared. Perhaps the only chance of recovery lay where the chute fanned out, cutting through the scrub to the river – not today though. Naturally my mind was juggling the probability of damage incurred to the horns and skin.

On my arrival back at the hut John and Joy could not get a word in edgeways until I had related the day’s events. I was still pretty hyped up. John finally proclaimed that his day had not been in vain, as he had found the thar responsible for the sign above the lake. This area is just visible from the hut and as the last of the day’s sun highlighted the faces, the thar were easy to spot even at that distance. Another bonus was on another spur back towards us, we found another mob including two bulls.

The weather was too good not to make the most of it. My shot and unrecovered bull was going nowhere and could wait another day. Gaining access is never as easy as predicted in these conditions. This was the cold side of the valley and it was really noticeable. Sweat chilled on you very quickly. The main battle for height was over once we gained a wind-swept spur. Here tussock poked through, the snow was crusted and harder, so the going became easier. Thar started showing up opposite us. They were above the lake and luckily they weren’t too perturbed by our presence. Our immediate attention though, was the mob somewhere higher up on our spur. Scattered sign appeared where they had dropped down to feed and became more prevalent as we neared their living area.

By now we should have made contact. There weren’t many places left. At that moment the sun poked its nose over the far ridge and immediately the thermal switched uphill. We were caught with no chance of an undetected approach. A nanny’s head appeared from behind the last unchecked fold on the face. That dreaded shrill whistle sounded and then they were moving. It was more haste less speed as we tried to push uphill. John opted for a sidling route under an enormous boulder. I stayed on the spur frantically trying for traction on rock covered with a veneer of snow. By the time the thar were in sight they had gained 250 metres. I looked around for John. It was his shot. Later he said he hoped the thar would go left – they went right. Under the circumstances I did not hesitate. There were fifteen of them, two bulls in tow.

I held high on the shoulder of the biggest bull and got a real surprise when he was poleaxed. The 100 grain Hornady .243s were performing well. I quickly bowled two nannies and watched their paths as they slid into the basin. The bull will spend the winter frozen to the hill. He acted like a snow plough and moved only a few metres. My rifle rest had been the snow cornice on the lip of a vertical drop with no access to the ground he lay on. I gave a grimace – so far two bulls shot and neither in hand.

I caught up with John back down the spur. He was videoing the magnificent scenery. He had heard the shots alright. We both then descended until we were able to sidle into the shot nannies. Once the skinning was finished, we headed down with the intention of John collecting a thar, if the other mob were still in residence. They were. My earlier shots had probably sounded like a rock fall or avalanche. We now had the advantage of being in the shade, while they were looking into a lowering sun and this enabled us to get within 150 metres. John gave me a quick course on using the video, then proceeded to do some fine shooting.

Again you wouldn’t believe our luck. The snow was so soft that the carcasses were held in its grasp. It might seem senseless shooting game when there is only a slim chance of recovery and this is where thar hunting can be at its most frustrating. There must be countless numbers of unclaimed trophies left in the Southern Alps.

Our choice not to follow our ascending tracks meant slow progress on a new path through a maze of huge boulders, expecting at each step to plunge through the bridged snow.

Once above the lake, we had the option of dropping straight down or taking a longer, scrub bashing route. We took the former. While the soft snow hampered climbing, it made it possible to drop over spots you wouldn’t dare otherwise.

The hard work was over once we hit our old tracks on the lake.

We stopped there and had a breather. I had a job to do on my rifle as the last shot I fired resulted in a stuck bolt. I managed to thump it open and there was no sign of excess pressure on the case. Earlier in the day the barrel had filled with ice and even the bolt face was layered with it. Normally this can be prevented with tape over the muzzle which I had neglected to do.

A real bonus on this trip, especially as it was mid winter, was having Joy back at the hut. With the fire stoked and a brew never far away we were being spoilt. It rounded off the tiring days nicely.

An attempt to recover my first bull took precedence the next day. We managed a dryfooted river crossing, then walked down the flats until reaching the rock fan. A dry water course up the left edge aided the first part of the climb. Looking up I could trace the bull’s approximate flight path. With all that momentum we had hoped to find him well down. That was a fallacy and I shouldn’t have expected it to be so easy. There was a puzzling lack of evidence of hair, blood or scuff marks. John scoured either side of the fan while I just kept climbing, entering the gut where it pinched tight. Luckily one side had a small amount of growth on it, enough to get a hand and toe hold on. Old avalanche snow debris had collected in several areas. While standing on one of these to speculate about the situation, I noticed what appeared to be a crater to one side. My heart jumped and again I felt that gut reaction. He was in there alright, completely submerged, anchored solid by the crushed snow around the edge. The ice axe was needed before saviour for there was not a mark on him. I yelled down to John to confirm my finding. I soon whipped off the headskin and horns. He represented a respectable trophy at 310 mm, but he won’t be remembered for the horn size but rather by the effort required to procure them.

John was busy glassing the opposite faces. It was chamois country, but strangely we had seen none this trip, not even a slotted print. On my two previous trips here in the early 1980’s it was all chamois and very few thar.

Our fortune with the weather ended. We spent a day hut-bound as a scoff and rest interlude. The hut’s log book, dating back to 1984, made interesting reading. This valley is quite a popular hunting and tramping destination. All the hunting parties were getting onto animals. The thar population was increasing, boding well for the recreational hunter, so long as a check on numbers is maintained to keep the land management people happy.

Day two dawned wet and mist) with a further dusting of snow. At John’s suggestion we used the mountain radio to request an early pick up. We were due out the next anyway and the weather forecast for a deteriorating outlook. The reply was, weather permitting, be ready 2pm. We were ready and waiting, one eye on the fog, an ear cocked for the sound of a jet engine. Next thing it was all go as we hurriedly piled gear in while the pilot uttered about the conditions and not messing about. One last glance inside the hut for forgotten items and we were away.

As a footnote to our departure it was fortunate we made it out that day as on the days to follow the country was hit by one of the biggest snow storms that lashed us that winter.

This is where huts, like the Horace Walker, are the greatest survival assets mountains can have.

Winding down from these trips always leaves withdrawal symptoms, cured only by poring over a map planning next year’s hunt.

SHARE YOUR BEST PICS #NZRODANDRIFLE