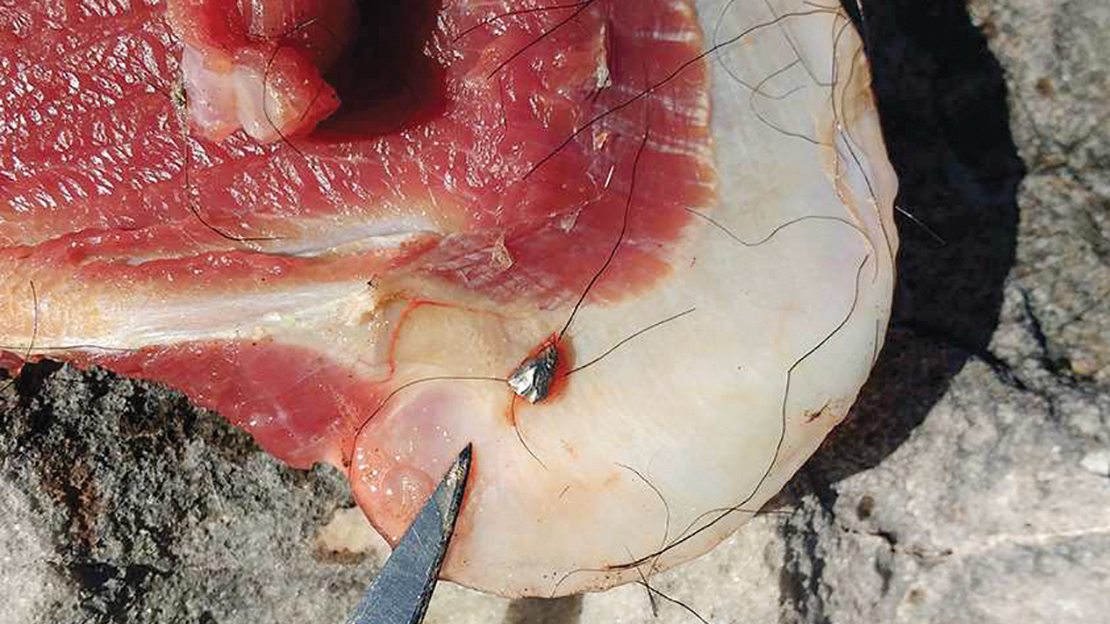

In 2009, I was cutting the front quarter of an animal apart and found a small lead fragment behind the shoulder blade. I thought, “I definitely don’t want to be feeding that to the kids.” We all know that eating and inhaling lead is bad for your health.

Over the last ten years, there’s been a lot of research done outside NZ examining lead ammunition use in hunting and culling. For the past six years, our team at the Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology has been part of an international consortium researching the use of lead ammunition in hunting. This article shares some of our findings and what we know about the use of non-lead ammunition outside NZ. The goal of this article is to explain why certain countries are moving to non-lead ammunition and how NZ and the NZ hunter fits into these global changes.

Why Was Lead Used in Ammunition?

From manufacturing, ballistics and price perspectives, lead is an excellent material for bullets; it’s cheap, it can be melted at relative low temperatures, it’s dense and soft, and lead also deforms on impact when used as a bullet. Since 2004 in NZ, and 1991 in the United States, hunters haven’t been allowed to use lead ammunition to hunt waterfowl near waterways. The reason for this restriction on lead use was because the spent lead shot dropped into the bottom of the waterway, and waterfowl were eating the lead shot as it’s the perfect-sized grit for their gizzard. The only exception to this restriction on lead use near water is the .410 gauge in NZ.

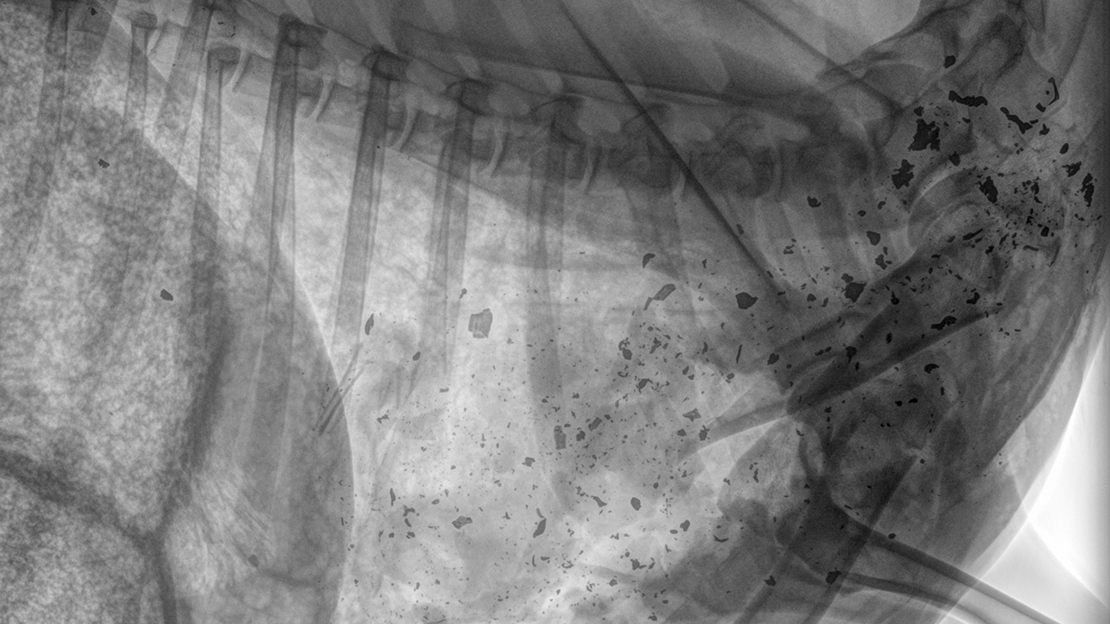

Entire countries, such as Denmark, have moved to reduce the amount of lead used in hunting because of the risks of lead poisoning to animals. These shifts away from lead have included centrefire rifle ammunition as well. The reason for including centrefire rifle ammunition is that overseas studies have shown when animals are shot with high-powered, lead-core bullets, 50-70% of the bullet mass is retained with the base of the bullet, yet the remaining small pieces (30-50%) are dispersed around the wound channel as hundreds of small fragments. Most of these fragments are under 5mm in size. The amount of bullet fragmentation depends on shot placement, bullet construction, calibre and load characteristics.

The Effect of Lead on Birds

The classic example of limiting lead ammunition for hunting because of the risk to other animals is the near extinction of the California condor. In 1982, there were only 22 condors left. Because there were so few birds remaining, it was initially hard to determine what was killing them. However, they all had high lead levels and these birds only eat other dead animals. While, initially, the source of the lead levels in these birds was debated, isotope analysis identified lead ammunition as the source of the lead in the condors’ blood – isotopes are chemical markers that can be used like a fingerprint to identify where a specific element, such as lead, has come from.

A captive breeding programme was started, and the population is recovering; lead ammunition is no longer allowed when hunting in the range of the California condor. Similarly, just this year, it was reported that nearly half of the bald and golden eagles in the United States have high lead levels from lead ammunition.

Closer to home, during the recent tahr cull in NZ, the Department of Conservation moved to non-lead ammunition because kea are known to eat the meat (and thus potentially lead fragments) around the wound channel of shot animals. This type of lead exposure could be a reason that nearly all kea have high blood lead levels.

A New Zealand Hunter with High Lead Levels

When hunting a number of years ago, I met a fellow hunter, and while chatting, he mentioned he ate a lot of self-harvested meat. He’d been experiencing dramatic weight loss and frequent gout attacks.

He’d considered arranging for a blood lead level test because he’d found several lead fragments while processing animals he’d shot, but he’d not yet had the test done. We arranged for his blood lead levels to be measured and they were extremely high – about 15 times the level of concern. The local District Health Board became involved with this hunter’s case, and they couldn’t identify any occupational or domestic source of lead.

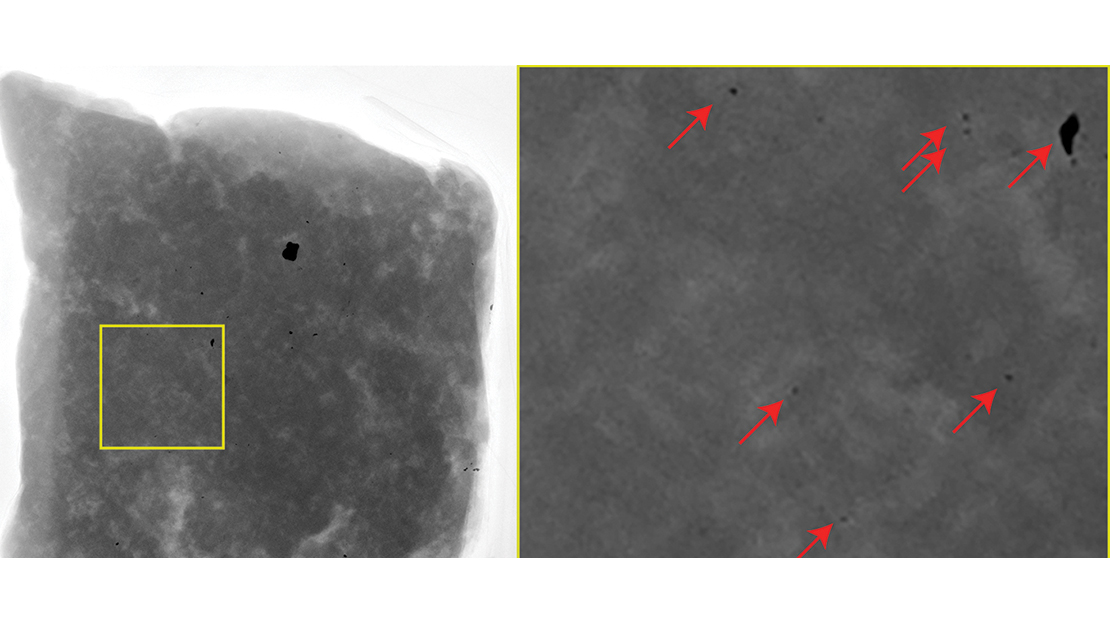

We took some mincemeat from his freezer to Pacific Radiology. When we shared the results with him, he was shocked to see small pieces of metal throughout the mincemeat he’d been eating.

We taught him to reload, and he shifted to non-lead ammunition. He continues to eat meat he’s shot, and his blood lead levels have been improving since the shift to lead-free ammunition.

Even a little lead is bad for your health – there’s no safe level of lead exposure. Unfortunately, the early signs of lead exposure aren’t specific and can include weight loss, fatigue, headache, irritability, memory impairment and stomach pain. The human body isn’t good at getting rid of lead; it tends to accumulate it, and as such, problems with elevated lead levels slowly build until they ultimately result in a health issue.

Meat Contamination Overseas

Nearly all studies looking at lead levels of meat from animals shot with lead ammunition are from the United States and Europe. In these studies, the percentage of mincemeat samples contaminated with lead can vary from almost zero to as high as 89%.

Recently, a long-term monitoring programme in Minnesota, USA reported that about 7% of donated venison has some lead contamination when screened by X-ray (this screening is required for venison donation programmes). X-ray screening is cheap and quick, but it only picks up the largest visible lead fragments; another technique called Inductively-Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) measures the actual amount of lead in a sample even if the pieces are too small to see by X-ray – the disadvantage of this technique is that samples need to be minced and it’s more expensive.

New Zealand Hunting is Different

It’s important to remember that hunting in NZ is dramatically different from other places in the world. It isn’t appropriate to simply think that in NZ, there’s the same level of lead contamination in lead-shot meat as there is in other places. For example, in parts of the United States, deer hunting with a firearm is limited to only a few weeks a year and you’re only allowed to use shotguns with slugs. Obviously, shotgun slugs behave very differently from centrefire rifle bullets when impacting an animal.

Additionally, in many parts of the United States, wanton waste of game meat is a crime, and you can go to jail for not harvesting all the meat from an animal you’ve shot. That situation is different from hunting in NZ where some hunters will only take the choicest meat cuts.

Based on what we know, there may or may not be a risk of lead exposure to NZ hunters and their families; we don’t have enough information yet to be sure, but our group is working to determine if the risk is high.

Studies Outside NZ Have Reported Lead-Contaminated Meat Samples

Studies in other countries have shown lead in meat harvested after killing with lead bullets. If you Google the title for these studies, they’re a good place to start research and free to access.

• Fragmentation of lead-free and lead-based hunting rifle bullets under real life hunting conditions in Germany. (Select the PMC Free link.)

• Lead bullet fragments in venison from rifle-killed deer: Potential for human dietary exposure.

• Comparison of lead levels in edible parts of red deer hunted with lead and non-lead ammunition.

Packrafting Samples Out of the Bush

As most organisations that fund our research aren’t familiar with hunting, late last year we needed pictures of the anatomical areas where lead would likely be concentrated if shot with lead bullets and examples of how to identify areas where lead would be concentrated.

For this project, we needed to bring the whole animal out of the bush, and because most hunters target deer, this was the animal we needed. We don’t have the budget for a helicopter, but we do have access to two packrafts. We spent a few hours scouring the map looking for rivers we could use to raft out an animal using our gold-standard approach: a three- to four-hour tramp in with no tracks or roads nearby.

We identified several catchments as options and waited for the weather window we needed to raft out some heavy weight; specifically, we were waiting for a fine spell after a good rain. In October, the perfect storm system came.

As our photographer and I drove south from Nelson, it was clear it was turning out to be a more thumping weather system than anyone had predicted. We parked the car and started walking up the river in a downpour. After four hours and having to use the packrafts to cross the river multiple times, the rain finally stopped as we arrived just before the change of light at a confluence we’d identified on the maps as a suitable base camp. Wet and cold, we crawled into our tents hoping the weather prediction was correct.

We woke the next morning, ate a quick breakfast and grabbed a packraft to cross the river to a section of river flats we’d identified upstream. When we got down to where the river was last night, we were surprised to discover the river was gone! What we’d followed up was an ephemeral tributary, and with daylight, we could see we’d been camping on a large, temporary island – definitely not the place we’d have chosen to spend the night if we’d known.

After about a 1km walk up the river flats, we entered a system of terraces with a small stream running along the base of the mountains. It was a perfect place for stalking with patches of bush intermixed with large sections of lush grass flats. After stalking along for about an hour, we heard a splash ahead in the stream and saw a flash of brown. A spiker had crossed the stream and was feeding just beyond a small patch of bush on the grass flats. I climbed down into the stream and rested the rifle on the bank. About 50m away, he fed towards the patch of bush and out of sight. After a few minutes of anxious waiting, he turned and walked out broadside presenting the perfect shot.

From both our work and the work of others, we know that most lead fragments from a bullet are deposited within a 30 cm diameter of the wound channel. If you take your thumb and place it in the entry/exit hole and make a circle with your fifth finger, that’s the approximate area where 95% of the lead will be found. Imagine a tube between the bullet entry and exit holes; the volume that this tube contains should be avoided as it has the greatest risk of lead contamination. The challenge is that if the animal is quartering or head-on, estimating the contaminated area gets to be difficult, especially if there’s any bone impacted. That impact can cause large fragments of lead to sheer off the bullet base at unexpected angles.

Chamois and Wound Channel Identification

This summer, we needed to collect examples of real-world, ideal shot placement on introduced animals in NZ. We also needed images showing how to identify the wound channel location in the field, identify factors that might alter the wound channel, such as hitting bone, and pilot the technique we’d developed for collecting meat samples from hunters. Most importantly, we had to finalise the technique we would use to determine where the wound channel was located depending on if the animal was shot in different quartering positions and from different elevations.

After a few lunchtime consultations, we decided that chamois or tahr would be the ideal animals for this collection because of the mountain terrain and the fact that they live in mobs. Using our standard technique of finding a location with a river crossing and no marked tracks or roads nearby, we identified several catchments that looked promising for chamois. After two cancellations due to weather, our photographer and I finally had a good weather window.

Following the walk in, we arrived at a small tarn in a hanging valley surrounded by promising chamois territory.

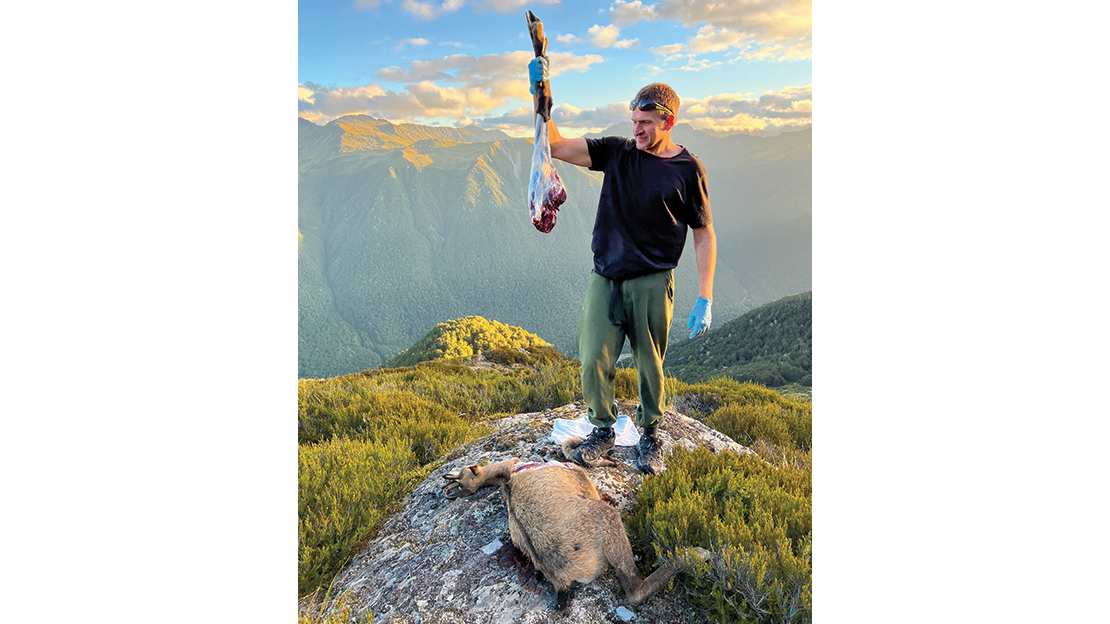

After dinner that night, we climbed to the top of the closest ridgeline and glassed surrounding valleys, but there was no sign of chamois in the catchment. We started the walk back to camp thinking we’d selected a valley without animals. About halfway back, we spotted a lone chamois on the north ridgeline watching us. Ducking behind a large rock, we watched the confused animal trying to sort out what we were. A quick view with the binoculars revealed a lone, mature doe; it took a couple of steps towards us providing the perfect head-on shot that we needed for an example. With no time for the rangefinder, we estimated her to be about 250m away and 100m above us. I steadied the rifle on the pack on top of the rock we were behind, took a few deep breaths, slowly exhaled and squeezed the trigger. The animal dropped on the spot and fell off the cliff making our recovery much easier. We now had one of the examples we needed, and the salvageable meat was recovered.

The following morning, we woke to a cracker day and headed north back up the ridge where we’d seen the doe the night before. Glassing the basin, we quickly picked up a buck about 700m away on the other side feeding away from us. As we climbed the spur, hidden from the animal, it quickly became clear that we were either going to risk certain death along the rock cliff on the backside of the ridge or risk spooking the animal by sneaking along the gentle tussock slope exposed to its view. We decided to risk spooking the animal. As we skylined ourselves coming over the ridge, the buck whistled and bounced off over the other spur.

Continuing to the next basin, we spotted a lone chamois next to a scree slope. After watching it for a few minutes, we noticed it kept looking back towards a small grassy area and rock knob. Following the line of that knob, we spotted another chamois, then another; eventually, we counted 12 about 1km away and below our current position.

We decided to double back on the main ridgeline and follow a scree slope down to a tarn and a small rock outcrop that looked to be about 150m away and above the mob.

After an easy scramble, we arrived at the backside of the rock outcrop. I dropped the pack, putting the bullets in my pocket – there are some disadvantages to having a single-shot rifle. I climbed a few metres up the rocks and crawled over the ridge to see the mob of 15 chamois – young bucks and does with a couple of kids. We needed to collect a quartering-towards, quartering-away and front-shoulder shot.

Arranging the bullets on a patch of dry moss on the rocks, I braced myself and lined up on a lone doe that was perfect for the front-shoulder shot, but I needed something to put under the rifle’s forestock to get a good rest. I was hesitant to risk climbing down to retrieve my pack – especially now that I was braced in a good shooting position. So, I took off my shirt, bunched it into a ball and placed it under the forestock like a sandbag. Perfect! By squeezing the balled-up shirt, I could adjust the elevation.

I lined up on the standing doe, exhaled and squeezed the trigger. She dropped, and the other chamois stood, looking around. I removed the case and reloaded. A young buck was standing quartering towards me. I aimed just to the front of the shoulder and slightly high to compensate for the elevation. Exhaling, I squeezed the trigger. He dropped. Removing the case, I reloaded.

The mob was now starting to get nervous, and some began to move off. I spotted a lone doe walking away and followed her shoulder with the crosshairs; just before she started down the scree slope, she stopped and looked back … just enough time for me bring the crosshairs slightly back to compensate for her quartering away and to get a shot off. After the shot, I looked at where she’d been standing but couldn’t see anything. The shot had felt good, but I immediately started to question myself.

I collected the cases, put my shirt back on and went to pick up my backpack. It was a short walk down to the first chamois. When I reached her, I could see the blood from the third one, and the doe was lying just at the top of the scree slope. We had the three examples we needed.

The walk back to camp that evening was slow with a heavy pack. Rounding a corner, we spotted a lone chamois on a knob looking down over the valley – the perfect ending to a beautiful day.

Measuring Lead Fragments in Animals

Five years ago, the hunter with high lead levels in his blood had given me his remaining copper-jacketed lead bullets. While we don’t know exactly the brand or type of bullets they were, he’d thought they were frangible varmint bullets. I pulled his bullets and reloaded into a cartridge for an older gun that I have. With these bullets, we headed into the open country. I shot a series of goats, and we measured the lead levels in the four quarters of the animal. We found that nearly all the lead was isolated to the front quarters of the animal.

If you’ve made a good shot on an animal in the front quarters and you’re at all concerned about the risk of lead exposure, just take the back quarters. As hunters, we usually listen to the bullet manufacturers and accept that some bullets are designed to better retain their mass while other bullets are designed to fragment, such as the frangible varmint loads. However, there have been controlled studies reporting that, regardless of the bullet design, if the bullet contains lead, it’s likely to fragment. Keep in mind that even if your bullet advertises 90% weight retention, that 10% is going somewhere else inside the animal.

Growing the Hunting Community

Hunting NZ’s introduced animals is the best way to selectively manage animal populations, and we as hunters need to do everything we can to grow the hunting fraternity. DOC has recently acknowledged this situation with the movement towards hunter-led conservation efforts. Game animal management in NZ is different to managing game animals in other countries, and organisations such as the Sika Foundation have done excellent work demonstrating what’s necessary (usually taking females from the herd) to increase the quality of a herd of animals.

Regardless of the results of our research, to properly manage NZ game animals, we need the hunting community to grow, and we don’t want people to be nervous about eating animals they harvest. Fortunately, if it’s found that there’s lead in some of the meat hunters harvest, this provides the information and science-based evidence hunters need to shift to non-lead ammunition, if they’d like to, while still managing the game species appropriately.

Furthermore, if people still want to use lead ammunition, there are other ways to reduce the risk of lead exposure such as (ethically) head shooting or staying more than 30cm in diameter away from the wound channel when harvesting meat.

Is Non-Lead Ammunition a Good Alternative to Lead?

There have been a number of scientific studies to measure if non-lead ammunition is as effective as lead ammunition at killing animals. If you Google the titles of the articles below, these are well-done studies and free to access:

• A comparison of fragmenting lead-based and lead-free bullets for aerial shooting of wild pigs.

• Hunting of roe deer and wild boar in Germany: Is non-lead ammunition suitable for hunting?

• Efficacy of non-lead ammunition for culling elk at Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

• Are lead-free hunting rifle bullets as effective at killing wildlife as conventional lead bullets? A comparison based on wound size and morphology.

• Unleaded hunting: Are copper bullets and lead-based bullets equally effective for killing big game? (Select the PMC Free Full Text link.)

Free Testing for Lead in Mincemeat

Because the potential risk for lead exposure through eating lead-shot meat is unknown, the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust have supported a project to determine the risk of lead exposure to NZ hunters. All you need to do is send a package of frozen mince from an animal you’ve shot with required information and the sample will be analysed for lead levels. We can only analyse minced meat because we’re using the ICP-MS technique. The trust pays for the analysis and freight, so there’s no cost to you.

If you use lead-free ammunition, your samples are still needed to allow a comparison between types of ammunition. You’ll receive a copy of the results from the analysis. Details for participating in the study are available by emailing Research.Admin@nmit.ac.nz with your contact details.

Photographs by Tim ‘Scream’n Vegan’ Norman. Also, thanks to Gareth Parry and Jordan Hampton for their contributions.

SHARE YOUR BEST PICS #NZRODANDRIFLE